Breaking Down Prednisone Too Quickly May Short-Circuit Its Benefit for Rare Neuromuscular Disorder

February 15, 2024

Myasthenia gravis is a rare disorder of the nervous system and muscles that affects the immune system. For most people with myasthenia gravis, prednisone — a steroid used to reduce inflammation (corticosteroid) — can be an effective treatment. But for more than 20% of patients, prednisone does not work. Scientists have looked for a way to predict who the drug might help and who will need a different treatment.

Examining myasthenia gravis patient blood samples from an earlier three-year clinical trial, researchers with the Myasthenia Gravis Rare Disease Network (MGNet), part of the NCATS-led Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, may have found an answer.

MGNet scientists studied how patients in the trial processed (metabolized) the drug, looking for chemical breakdown products in the blood. They also measured blood lipids, which are fatty compounds that carry out essential roles in cells. The scientists discovered that several chemicals, or metabolites, produced when the body breaks down prednisone could, when used together, predict when the drug worked well in patients.

“The data appear to indicate that people who metabolize prednisone too quickly may not give the drug enough of a chance to work,” said MGNet principal investigator Henry Kaminski, M.D., who treats patients with the disorder at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Kaminski and his MGNet colleagues published their results in PLOS ONE.

Prednisone is a proven treatment for myasthenia gravis, Kaminski said. It is not expensive, is widely accessible, and tends to work in four to six weeks. But steroids come with side effects, including weight gain, facial swelling and mood changes.

“We’d like to know which people won’t respond to treatment so we can consider using other medications, such as drugs that suppress the immune system and biologics,” he said. There seems to be a similar percentage of people with other autoimmune disorders — such as lupus, asthma, ulcerative colitis and rheumatoid arthritis — who do not respond well to prednisone.

In 2016, Kaminski, the University at Buffalo’s Gil Wolfe, M.D., and their colleagues reported the results of a clinical trial that compared thymectomy (surgery to remove the thymus gland) and treatment with prednisone to prednisone alone in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trial, funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), found that the surgery reduced the need for steroids. NCATS and NINDS co-fund MGNet.

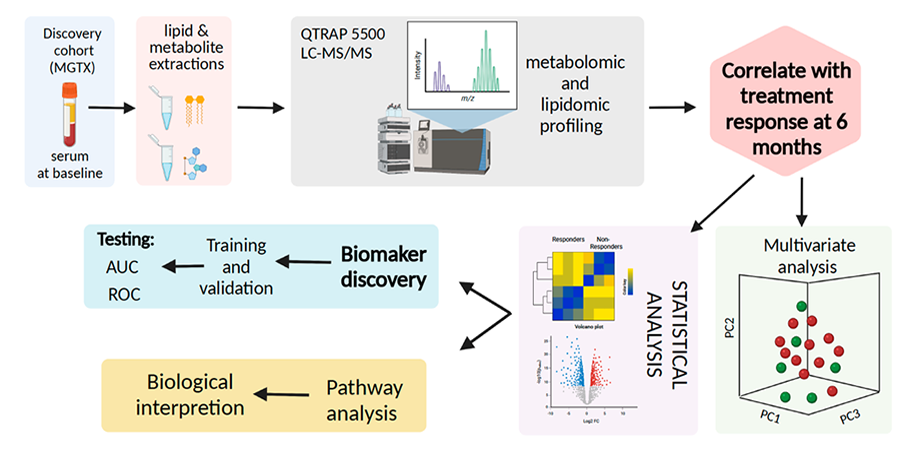

MGNet researchers were able to get blood serum from nearly all the trial participants. The researchers wanted to identify markers in the blood samples at the beginning of the study that could be linked to response to prednisone treatment after six months. They looked at lipids and metabolites in the two clinical trial groups at the start of the study and again six months later.

The findings suggest that lower levels of certain metabolites and lipids at the start of treatment may predict poor responses to prednisone.

The researchers also looked at the biological pathways involved in how a body processes the drug. Pathways are like chemical reaction relay systems that carry out specific tasks or functions. The scientists saw differences in activity between patients in the trial who responded to treatment and those who did not.

“An important result came out of our pathway analysis,” Kaminski said. “We showed that drug metabolism correlates to steroid treatment unresponsiveness. It appears that it’s how the prednisone is metabolized that’s critical in determining treatment response.”

Kaminski said the results suggest that prednisone is broken down by the body more quickly in people who are not responding to treatment. They may not be getting the same amount of the drug.

“What’s surprising is the ability to see these metabolites change in an unrelated group of people. This shows they are processing prednisone differently,” said co-author Linda Kusner, Ph.D., at The George Washington University. “They eat different food, have different stressors, exercise at different levels and take other medications that all affect the metabolites in the blood. Yet we see similarities among them due to prednisone.”

Other factors, such as genetic differences, could affect how patients respond, Kaminski noted. The researchers plan to show how accurately the steroid treatment-response marker predictions are. The results could lead to screening tests for patients. They might also help doctors predict the best treatments for other autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

“A better understanding of prednisone metabolism will help in personalizing treatment approaches for patients,” Kaminski said.