Working Together Is the Name of the Game at Rare Disease Day at NIH

April 4, 2019

“You aren’t heard as much as you need to be, so you kind of feel left in the background,” said Tesha F. Samuels, a panelist at Rare Disease Day at NIH who shared her experience with sickle cell disease. As a child, she and her mother would go from hospital to hospital to find relief for her pain. “What if, in 1990, my mother and I had a Rare Disease Day, where we knew that there were excited scientists and patient advocates looking for us?”

Ms. Samuels’ sentiments reflected those of many patients and families attending the 2019 Rare Disease Day at NIH on Feb. 28. NCATS and the NIH Clinical Center co-sponsor the yearly event to raise awareness about rare diseases and connect researchers, regulators, patients and patient families to advance research and efforts to develop therapies.

NIH Clinical Center patient Tesha F. Samuels discusses her experience with sickle cell disease during the “No Disease Left Behind, No Patient Left Behind” panel session at Rare Disease Day at NIH on Feb. 28, 2019. (Daniel Soñé Photography)

Panel discussions covered collaborative approaches to rare diseases research, registries, rare cancers and gene therapy/gene editing. They highlighted NCATS’ philosophy that to maximize progress in rare diseases research, investigators and patients must work together. And together they were, with a record audience of more than 650 in-person attendees and 1,200 webcast views of this year’s event.

Learning from Patient Advocacy Groups

Investigators and patient advocacy group (PAG) representatives on one panel shared how this collaborative approach works in the NCATS-led Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). The Network currently comprises more than 20 consortia, each consisting of medical research centers working with PAGs to study several related rare diseases.

For example, the Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR) studies eosinophilic diseases, in which eosinophils — a type of immune cell — build up in the digestive tract and damage the tissues. Eosinophilic diseases are painful and lifelong, and they can make it hard or impossible for people to eat many foods.

One of the consortium’s PAG representatives, Ellyn Kodroff, started the Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease (CURED) after her daughter was diagnosed with eosinophilic disease in 2003. She recalled the time researchers and doctors asked for her thoughts on a research project at her first consortium meeting. She wondered whether they would listen to her.

Seema Aceves, M.D., Ph.D. (left), and Ellyn Kodroff speak about how researchers, doctors and patients can work together in rare diseases research. (Daniel Soñé Photography)

“Right in front of me, they changed gears of where they were going with the research, because now they could understand the patients’ needs,” Ms. Kodroff said.

In turn, Ms. Kodroff and other PAG representatives bring information on clinical trials to the patient community and explain the importance of participating.

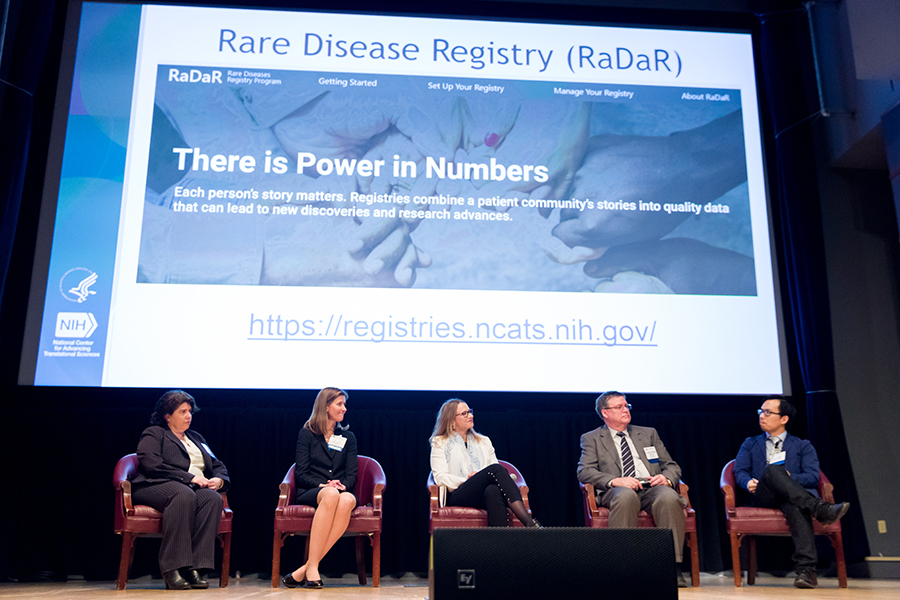

Translating Patients’ Stories into Data

Patient registries can help record patients’ stories to aid researchers in understanding diseases, designing studies and even changing clinical care. These registries can contain medical details as well as information about patients’ experiences — such as their quality of life, priorities and needs — that test results may not capture.

“Registries are a way for patient advocacy groups to take the stories within their community and use that as a tool to describe them in a way researchers, regulators and decision makers can understand and interpret,” said Eric Sid, M.D., M.H.A., presidential management fellow in the NCATS Office of Rare Diseases Research, who moderated a session on the use of patient registries.

Emily Milligan, M.P.H., executive director of the Barth Syndrome Foundation, explained why the foundation created a registry in 2006. Barth syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that mainly affects boys and can cause problems with the heart muscle, the immune system or other parts of the body.

Investigators used the foundation’s registry data to understand more about the syndrome and how it progresses over time. The registry was also an invaluable tool for engaging the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), including at a patient-focused drug development meeting last summer.

Panelists discuss the power of harnessing patient data through registries at Rare Disease Day at NIH. From left to right: Jeanine D’Armiento, M.D., Ph.D.; Janet Maynard, M.D., M.H.S.; Emily Milligan, M.P.H.; Forbes Denny Porter, M.D., Ph.D.; and Eric Sid, M.D., M.H.A. (Daniel Soñé Photography)

“The registry data corroborates what FDA heard in the patient testimonies, and that helps to accelerate its decisions around approval of drugs,” Ms. Milligan said.

Ms. Milligan and the Barth Syndrome Foundation lent their experience when the precursor to NCATS was looking at how to help other patient organizations set up registries. NCATS built on this pilot project to create the Rare Diseases Registry Program (RaDaR), which provides advice and best practices for creating and managing a registry.

Cancers Can Be Rare Diseases, Too

Cancer may not be the first thing that comes to mind when people think of rare diseases, but one in three to four people with cancer has a rare type. Rare cancers include, for example, all pediatric, brain and spinal cancers, as well as sarcomas, which affect connective tissues like bone, skin and fat. In addition, research and advocacy efforts for rare cancers are often grouped under efforts for more common cancers, at times leaving the rare cancer and wider rare disease communities disconnected. A panel on rare cancers, held at this year’s Rare Disease Day for the first time, sought to find ways for the two communities to work together more closely.

“Rare diseases and rare cancers suffer from the same of lack of infrastructure, interest and money,” said Corrie Painter, Ph.D., associate director of Count Me In, an initiative in which cancer patients make their genomic data freely available to researchers looking to find new treatments. “If we could find common ground to build that infrastructure, then all of us could leverage it at the same time rather than reinvent the wheel.”

One suggestion was to create common data models, which is a way of collecting information on patients that allows it to be used by others more easily. Another suggestion for improving research and awareness efforts in rare cancers was to educate both oncologists and patient advocates about clinical trials so that they could share the information with patients and improve clinical trial recruitment.

Leaving No Patient Behind in Gene Therapy and Gene Editing

Near the end of the day, the discussion turned to clinical trials of gene therapy and gene editing. In principle, these technologies could be applicable to many different genetic diseases. In a session entitled “No Disease Left Behind, No Patient Left Behind,” panel members talked about how to make gene therapy and gene editing trials available and accessible to as many rare disease patients as possible. A first step toward that goal is ensuring patients’ voices are heard.

John F. Tisdale, M.D., participates in the “No Disease Left Behind, No Patient Left Behind” panel session at Rare Disease Day at NIH on Feb. 28, 2019. (Daniel Soñé Photography)

“We really need to partner with the patients to figure out what is most affecting their lives and what they would like to see changed in the context of a clinical trial,” said John Tisdale, M.D., chief of the Cellular and Molecular Therapeutics Branch at NIH’s National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. “We’ve been trying to do that in the sickle cell disease space, but I think that across the board, we should do better.”

In sickle cell disease, a defective gene leads to misshapen red blood cells that get stuck in blood vessels, causing severe pain, stroke or other complications. A bone marrow transplant can cure the disease, but most patients do not have a matched donor. Several years ago, Tisdale launched a gene therapy clinical trial for patients with sickle cell disease. His sickle cell research was featured on 60 Minutes in March 2019.

The gene therapy allows adults who do not have a matched donor to use their own bone marrow stem cells. Doctors remove the cells, add the correct gene, and put the cells back into the patient. The few patients who have undergone the procedure through the trial are now making healthy red blood cells. Ms. Samuels, who is one of these patients, provided her unique perspective on the panel.

Another crucial issue for leaving no patient behind is understanding the barriers to taking part in a clinical trial for a gene therapy. Patients, family members and patient recruitment specialists on the panel discussed these challenges and possible solutions.

Alone Together

In his closing remarks, NCATS Director Christopher P. Austin, M.D., reinforced the need to work as a team and bring together complementary expertise.

“I hear every day how alone patients with rare diseases and their families can feel and how alone researchers studying rare diseases feel,” Dr. Austin said. “So let’s all be alone together and think about rare diseases as a gigantic and ultimately beautiful jigsaw puzzle.”