Ketogenic Diet May Offer a New Approach to Treating Alzheimer’s Disease

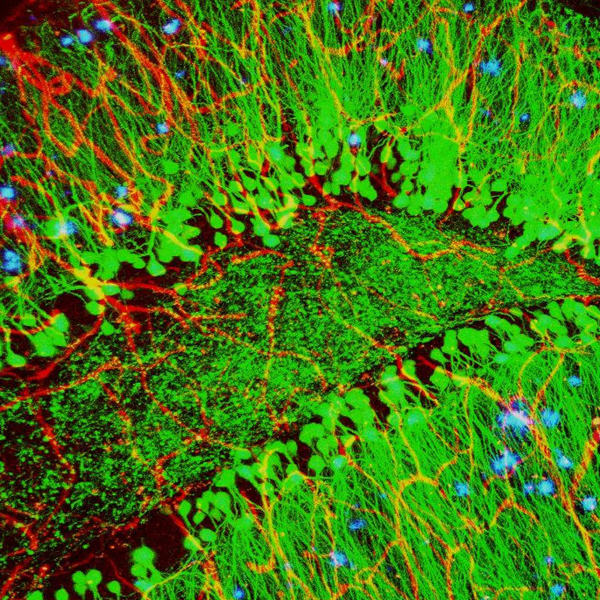

Along with blood vessels (red) and nerve cells (green), this mouse brain shows abnormal protein clumps known as plaques (blue). These plaques multiply in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and are associated with the memory impairment characteristic of the disease.

Credit: Alvin Gogineni, Genentech

March 22, 2022

The brain relies on glucose as its primary source of energy, but in people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the brain is less able to use glucose for fuel. Researchers at the University of Kansas, an NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program hub, recently explored the potential of another source of energy—ketones—to improve brain function in people with AD. Ketones are produced when glucose is in short supply and the body turns to fat as its main energy source. Although the brain’s ability to use glucose declines in AD, its ability to use ketones does not.

The research team, led by Russell Swerdlow, M.D., and Debra Sullivan, Ph.D., conducted a pilot study—the Ketogenic Diet Retention and Feasibility Trial (KDRAFT)—to assess the feasibility and cognitive effects of a ketogenic diet in individuals with AD. Ten participants with mild AD followed the ketogenic diet for three months, followed by a return to a normal diet for one month. Standard cognitive tests administered during the study showed that cognitive scores significantly improved after the three-month intervention. Test scores returned to baseline after the one-month washout period.

Participants with more advanced dementia dropped out of the study, suggesting that those with mild AD are better able to adhere to the diet.

The predominant theory about the cause of AD suggests that the build-up of the protein beta-amyloid in the brain disrupts communication between neurons and ultimately kills brain cells. Dr. Swerdlow’s research suggests that amyloid plaques are a result, rather than a cause, of AD and that defects in brain energy metabolism may be the underlying cause. The results of the KDRAFT study appear to support this hypothesis, although larger studies are needed. The research team, however, seems to have established proof of principle that fuel other than glucose can help restore energy metabolism in the brain.