Tissue Model Approach Provides Clues to SARS-CoV-2 Brain Infections

January 28, 2021

Although neurological complications are common in people infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19, scientists do not fully understand how the virus affects the brain. A team including researchers from NCATS, the University of Pennsylvania (Penn), Scripps Research Institute and Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute found that the virus appears to congregate in certain brain cells.

The work relied on the use of brain “organoids,” tiny 3-D tissue models of human brain development. Organoids, which are developed from human stem cells, can mimic important features of a human organ’s structure and function. NCATS is developing their use to help researchers better predict the effectiveness and toxicity of compounds and drugs. The team’s findings, published in Cell Stem Cell, could lead to new insights into both the virus’s behavior and its potential effects on the brain.

In March, NCATS scientists Wei Zheng, Ph.D., and Catherine Chen, Ph.D., began seeing evidence in both news reports and journal articles that the virus was affecting the brain. “We had seen indications that COVID-19 was a systemic infection and were hearing reports of patients showing neurological symptoms,” said Zheng.

Due to our experience with Zika virus, we saw an opportunity to bring different groups with unique expertise together and form a collaborative project team to use brain organoids to study SARS-CoV-2.

To investigate this further, Zheng and Chen took cues from a previous collaboration studying the neurological effects of Zika virus. In a 2016 report in Nature Medicine, a team of scientists — including Zheng — showed that brain organoids were a good model to study and test drug candidates for Zika virus infections. “Due to our experience with Zika virus, we saw an opportunity to bring different groups with unique expertise together and form a collaborative project team to use brain organoids to study SARS-CoV-2,” Zheng said.

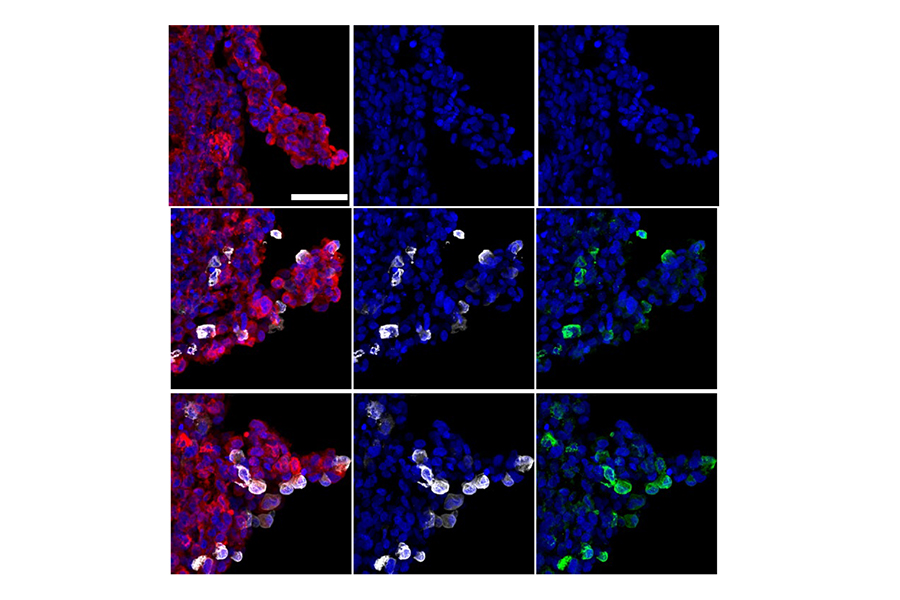

The NCATS scientists contacted their Zika virus research collaborators Hongjun Song, Ph.D., and Gou-Li Ming, M.D., Ph.D., at Penn, as well as other potential partners. Zheng and Chen made human organoids that mimicked a part of the brain called the mid-brain, whereas the Penn team already had organoids for three other brain regions that included different neuronal cell types. Penn researchers sent all four organoid types to Scripps Research Institute scientists, who subsequently infected the brain organoids and different types of brain cells with SARS-CoV-2. Sanford Burnham scientists also provided neuronal cells and cells from the brain’s choroid plexus for SARS-CoV-2 infection studies. The choroid plexus produces cerebrospinal fluid that protects and nourishes the brain.

The Penn team analyzed the infected organoids and cells to look for evidence of the virus. They determined that only a small percentage of brain cells were infected, and most of them were in the choroid plexus region of the brain. The increased viral infection was killing choroid plexus cells and neighboring brain cells. In the organoids with choroid plexus cells, it appeared that certain genes were working overtime to increase immune system activity, causing inflammation and cell death.

“The brain has been a black box regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection,” Zheng said. “Now we know that the virus infects just a small percentage of neurons. We don’t know the implications of that yet.”

As researchers try to understand these implications, organoids may continue to be a useful tool to better understand the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the human brain and test the effects of possible treatments.