Changing the Pill: Tackling Medication Adherence Through Innovative Technology

March 17, 2020

About half of all patients in the developed world don’t take medicines as prescribed. In the United States alone, that statistic contributes to 125,000 preventable deaths, 50 percent of treatment failures and 25 percent of hospitalizations, at a cost between $100 billion and $289 billion each year. In the developing world, where barriers may be multiplied, medication adherence rates are even lower. For example, preventive malaria treatments require multiple doses over several days across the community to maintain adequate immunity levels. Malaria causes nearly 500,000 deaths annually around the world, with most occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

Health care clinicians, public health administrators and researchers have all sought solutions to make taking medicine easier, including reminder apps and treatments combined into a single pill. A new idea came from researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): Extend the time drugs last in the body and decrease the number of doses needed.

With this goal in mind, Amy Schulman, Robert Langer, Sc.D., Giovanni Traverso, Ph.D., and Andrew Bellinger, M.D., Ph.D., founded Lyndra Therapeutics in Watertown, Massachusetts, in 2015. Their NCATS Direct-to-Phase II Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) award has provided pivotal support to help them develop and move toward commercializing a solution that could address the problem of medication adherence by “changing the pill instead of the patient.”

The team focused its attention on developing a new dosage form that could deliver a steady dose of medication(s) in the body for a whole week or even longer. The researchers then looked to an initial therapeutic application: using the platform to develop a long-acting dosage of an anti-malarial drug called ivermectin.

Ivermectin works by killing mosquitos when they bite people who have adequate levels of the drug in the bloodstream. But to reduce the prevalence of malaria in areas where it’s endemic, everyone in the community—which is often rural—must take the drug in doses high enough to reduce the population of mosquitos in the area. That’s where having a single, ultralong-lasting dose could make a difference.

A Pill That Stays Put in the Gut

Some injectables and implants provide long-acting therapeutic benefits, but an oral capsule that lasts more than a day has been a translational challenge. The Lyndra team had to overcome many translational hurdles and meet several requirements to develop the first oral dosage that can deliver medication for up to a week or longer. First, the dosage form needed to withstand the human gastrointestinal system’s rapid transit time and stay in the stomach for more than a day without blocking the passage of food. It would also have to be small enough to swallow and big enough to carry a large quantity of the medicine. In addition, it would need to withstand the acidic environment of the gut, yet eventually break down at a predictable rate so that it could pass out of the body.

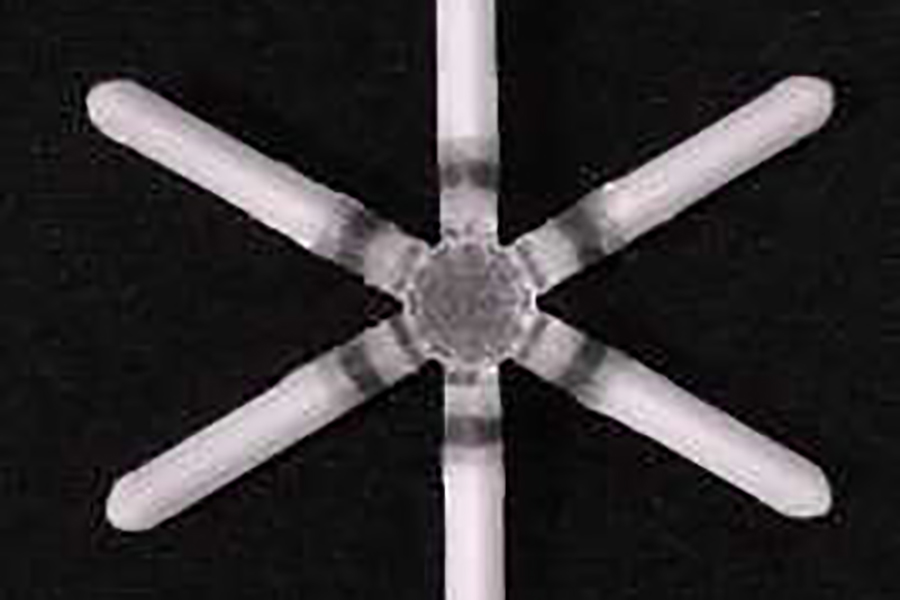

The solution the team created was a dosage form that changes shape in the gut. To patients, the dosage form looks like a familiar capsule—a fish oil tablet. Once it reaches the stomach, however, it blossoms into a star shape that is too big to pass through the valve that opens into the intestines but still doesn’t block food from getting through. This allows the dosage form to stay in the stomach, releasing a slow, steady dose of medicine, until the material breaks down and exits via the gastrointestinal tract, like undigested food.

Crossing the Valley of Death

The team had a lot of preliminary data from animal models, laboratory experiments and mathematical modeling that showed the pill could work. Still, they needed support to take the next step to develop the product and scale up manufacturing to create enough of it to run clinical trials. That meant finding sources willing to invest in the idea at a very early stage.

The Lyndra capsule expands into a star-shape dosage form upon reaching the stomach. (Lyndra Therapeutics)

This early period of research and development is often called the “valley of death” by translational scientists and is a tipping point where good ideas are at greatest risk. “Consultants and experts aren’t always willing to talk to you when it’s early; you have no track record,” said Bellinger, who noted another obstacle: “It’s a challenge when the product in development is not particular to a disease-focused area, but rather the creation of the platform itself.”

The NCATS SBIR program, which provides funding across a range of research priority areas in translational science, helps early-stage entrepreneurs bring their innovations to the commercial market. In the process, it enables the translational science process for small businesses so that new treatments and cures for disease can be delivered to patients more efficiently.

“Lyndra Therapeutics is a notable example of how small businesses working in the life science space can leverage the NCATS SBIR grant program to further their product development,” said Lili Portilla, director of the NCATS Office of Strategic Alliances. “Lyndra was able to focus the grant on the manufacturing of the drug delivery platform, which we considered very much aligned with our SBIR program priorities.”

Lyndra applied for and was awarded Direct-to-Phase II funding from NCATS to develop the product for an antimalarial treatment they had originally begun work on at MIT in animal models. The award supported the ability to create a product in quantities large enough to begin early-phase clinical trials and prepare for investigational new drug approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

NCATS SBIR Provides Crucial Support

“The NCATS SBIR grant helped us at a very critical stage. It was an important funding source, especially around our manufacturing ability,” said Bellinger.

The team found that, in addition to providing funding, NCATS opened doors for the young company.

“We talked to people at NCATS a lot, and they gave us good recommendations for engaging with other agencies such as the FDA,” explained Bellinger.

Once the company was able to share clinical trial results, more investors were interested. “The product we proposed to NCATS,” said Bellinger, “has now garnered significant support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. It’s absolutely alive and well and moving into clinical development.”

Building on its success supported by NCATS and other parts of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Lyndra was able to raise $60 million in Series B funding and start Phase I clinical trials for several programs.

“We are now a four-year-old company that has run a number of clinical trials, and we were able to get an early start on manufacturing clinical batches,” said Bellinger. “Clinical trials were hugely validating for us.”

Lyndra is testing the dosage form for a number of chronic indications, in partnership with a variety of investors and pharmaceutical companies. For instance, it has partnered with Gilead Sciences to develop and commercialize ultralong-acting oral HIV therapies and with Allergan to develop a once-weekly capsule for Alzheimer’s disease drugs. The pipeline now includes treatments for psychiatric disorders, transplant rejection, opioid use disorder and oral contraceptives.

“We are thinking about what the first commercial product will look like,” said Jessica Ballinger, chief operating officer at Lyndra. “In the next three years or so, hopefully, it will be getting to market. NIH has definitely helped us with our speed. I don’t think we could do it without the NIH.”