Breathing Easier: First Treatment for Rare Lung Disease Approved

In 1994, Sue Byrnes brought her daughter, newly diagnosed with a rare lung disease called lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), to Francis McCormack, M.D., a pulmonary physician-scientist at the University of Cincinnati. Byrnes wanted to know what, if anything, McCormack could do, but with scarce research on the condition and no existing treatments, he could offer little encouragement.

LAM is a progressive lung disease that mostly affects women of child-bearing years. In LAM patients, smooth muscle cells invade the lungs and grow uncontrollably. Over years, this abnormal tissue builds up and blocks airflow, making it increasingly harder for patients to breathe and carry out everyday activities. Typically, patients survive about 20 to 30 years after diagnosis. LAM is very rare, affecting only about 30,000 to 50,000 people worldwide, or three to five people per million. This number is likely higher, however, because the disease is greatly underdiagnosed.

Byrnes, frustrated by the lack of research and treatments to help her daughter, established The LAM Foundation with McCormack’s help. To date, its advocates have raised more than $20 million, collaborated with academic and government scientists, and stimulated much of the existing research on the disease.

In 2015, that investment paid off: In the most monumental victory to date for LAM patients, research coordinated by the Foundation and carried out with its scientific partners in NCATS’ Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) culminated in the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatment for LAM.

It Takes a Village

The road to this long-awaited success involved the Multicenter International LAM Efficacy of Sirolimus (MILES) Trial, based at the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and led by McCormack. The investigator-initiated, international clinical trial was unprecedented in size and scope for such a rare disease and was enabled by a seamless collaboration among RDCRN-supported scientists and LAM Foundation advocates.

A lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) patient (right) with her daughter (left). The daughter is preparing to enter college and, someday, contribute to understanding this disease for which treatment included her mother undergoing two double-lung transplants. (Frank McCormack, M.D./University of Cincinnati)

“The process had a huge learning curve at every level,” remarked Bruce Trapnell, M.D., a pulmonologist and professor of medicine and pediatrics who is the principal investigator of the RDCRN’s Rare Lung Diseases Consortium (RLDC), through which the trial was conducted. “We had never established this kind of network before by ourselves, and the teamwork among The LAM Foundation, the administrative team and our researchers was absolutely indispensable and a pivotal part of the infrastructure that made this possible.”

Because the limited number of rare disease patients can make gathering information and designing clinical studies difficult, collaborations among government, academia, industry and patient advocacy groups are essential to advancing knowledge and treatments for rare diseases.

NCATS, with its mission to make the translational process of science more efficient to bring more treatments to more patients more quickly, underscores the power of collaboration through programs such as the RDCRN. This network is designed to advance medical research on rare diseases by providing support for clinical studies and facilitating collaboration, study enrollment and data sharing. The RDCRN consists of 22 distinct clinical research consortia and a Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC). Through the RDCRN, which requires consortia to pair with patient advocacy groups as research partners, scientists from multiple disciplines at hundreds of clinical sites around the world work together to study more than 200 rare diseases. It was this team approach that enabled the multi-site LAM trial.

An International Undertaking

Earlier NIH- and LAM Foundation–funded studies using LAM cell cultures and animal models suggested that a signaling protein called mTOR becomes overactive in patients with the condition. Experts knew that the drug sirolimus — already approved to prevent organ rejection in patients receiving transplants — lowers mTOR activity, so they suspected sirolimus could be a potential therapeutic candidate for LAM. With help from The LAM Foundation and the RDCRN, the RLDC researchers designed the MILES Trial to test sirolimus in LAM patients. Pfizer, which owns sirolimus, donated the drug for the trial.

Because McCormack and LAM Foundation advocates had spent decades building a worldwide patient network, they knew to establish MILES study sites in geographic regions close to where LAM patients lived. With 13 sites across the United States, Canada and Japan, the widespread nature of the trial meant that teamwork among RLDC researchers, RDCRN personnel, study monitors and The LAM Foundation was crucial to success. Foundation members reached out to their worldwide network of patients to inform them of the study and recruit participants. This outreach resulted in the participation of 89 LAM patients, an impressive sample size given the incredibly rare nature of the disease. At the time, experts estimated that only about 800 people in the United States had been diagnosed with LAM, although that number now is 1,400.

RDCRN and DMCC experts provided a wide range of support, including helping with trial design; collecting, managing and analyzing the data; providing international and U.S. regulatory expertise; and training study personnel.

A trial of this magnitude would not have been possible without the infrastructure provided by the RDCRN. We simply would not have had the audacity to attempt it. The DMCC provided real-time troubleshooting and guidance throughout the process, said McCormack.

The Office for Clinical and Translational Research (OCTR) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center also helped manage the complex regulatory and logistical aspects of conducting an international, multisite trial. These duties included institutional review board negotiations and submissions, regulatory compliance, site monitoring, data and budget management and participant recruitment and management.

The Road to Approval

The trial results showed that sirolimus, taken over 12 months, stabilized patients’ lung function, reduced symptoms and improved quality of life. The research was published in the April 18, 2011, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. The team used the results of the rigorously designed trial to submit an application to the FDA for approval of sirolimus as a LAM treatment. In May 2015, the FDA announced its approval, making sirolimus the first-ever approved treatment for LAM.

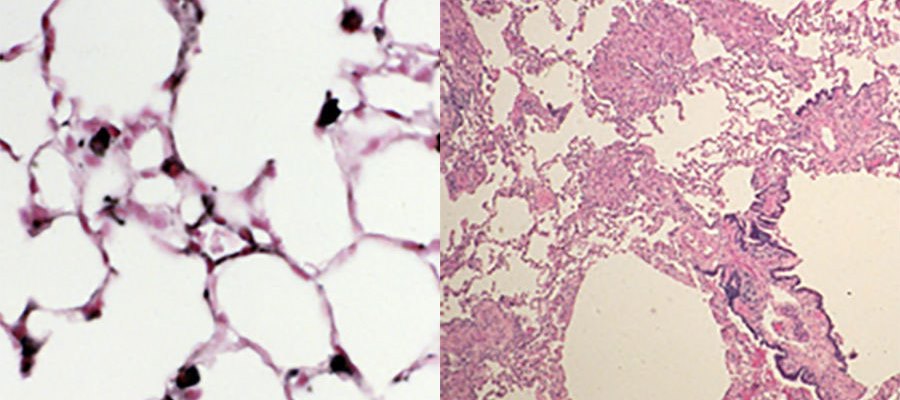

On the left is a normal lung and on the right is a lung affected by lymphangioleiomyomatosis. (Frank McCormack, M.D./University of Cincinnati)

“The approval of sirolimus as a therapy for LAM is a major milestone for LAM patients as well as for the broader rare diseases research community,” said Petra Kaufmann, M.D., M.Sc., director of the Office of Rare Diseases Research and the Division of Clinical Innovation. “This success shows that the RDCRN model is well-suited to overcome the unique challenges of rare diseases research and fulfill NCATS’ mission to help translate discoveries into better health.”

This approval means that more insurance companies now may cover sirolimus for LAM, making it easier and less financially burdensome for patients to access the drug. It also means that physicians will feel more comfortable prescribing the drug. Finally, FDA approval can facilitate government approval in other countries, in some cases making the drug accessible for the first time.

“Being diagnosed with a rare disease is difficult because for most rare diseases, there is so little research and no treatment, leaving relatively little hope,” said Andrea Slattery, board chair of The LAM Foundation and a LAM patient herself. “To have an FDA-approved drug after just 20 years of advocacy and research is hugely gratifying. It shows that our model of collaboration is working and allows us to serve as a beacon of hope for the thousands of other rare diseases that don’t yet have treatments, much less a cure.”

The RLDC team currently is designing a second clinical trial of sirolimus in LAM patients with milder disease. The hope is that giving a lower dose of therapy for a longer period of time during earlier stages of LAM, while lung function is still fairly normal, will halt progression to more advanced stages of the condition.

Although sirolimus stabilizes lung function for LAM patients, it is not a cure. The LAM Foundation and the RLDC will continue to work together to find one. According to Slattery, “Our motto at the Foundation is that collaboration is the key to the cure.”

McCormack certainly agrees: “The remarkable outcome of our collective efforts with LAM illustrates the great strides that can be made in rare diseases research when industry, clinical investigators, patient advocates and the government work together toward a common goal to improve the lives of patients.”

Posted March 2016

The MILES Trial was supported by grants from the NCATS Office of Rare Diseases Research; the FDA; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Pfizer; the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; The LAM Foundation; the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Vi and John Adler; the Adler Foundation; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Pfizer provided the study drug and funding for some study visit costs.