NCATS-Supported Researchers Find Cell Source Matters for Tissue Chips

February 2, 2019

Tissue chips — 3-D models designed to mimic human organs — hold immense promise to improve drug testing and development. Yet, as with many new technologies, there’s much to prove before they are widely accepted by researchers and industry.

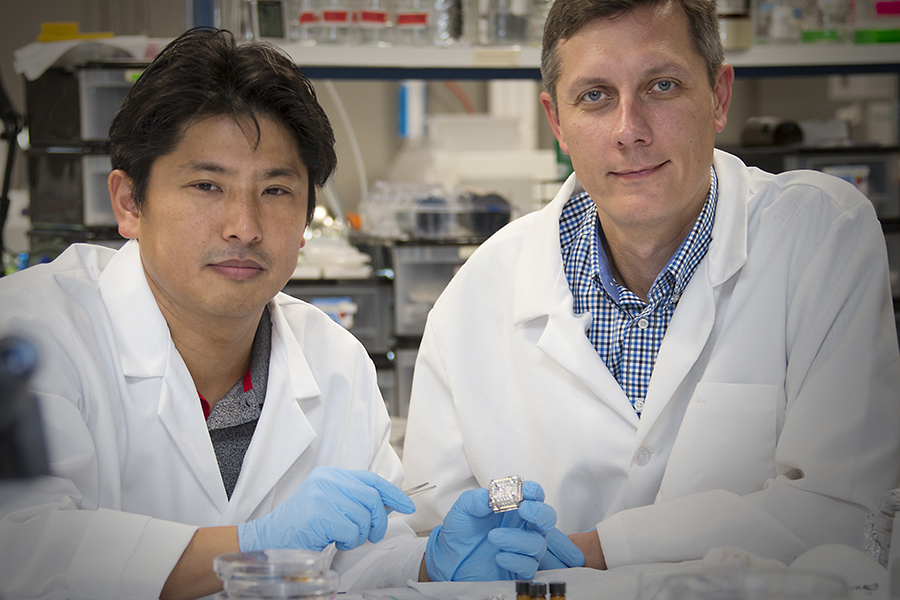

Texas A&M University researchers Arum Han, Ph.D. (left), and Ivan Rusyn, M.D., Ph.D. (right), studied the ability of a tissue chip to mimic a working human kidney. (Tim Stephenson, CVM Communications/Texas A&M University Photo)

To address some of the concerns, NCATS established Tissue Chip Testing Centers (TCTCs) to independently test and validate tissue chip systems. TCTC scientists aim to evaluate how well such systems work, whether they are reliable, and whether they can be reproduced, with a goal of helping them become more available. Recently, investigators at a TCTC at Texas A&M University evaluated a kidney tissue chip model developed by researchers at the University of Washington (UW) and at the company Nortis Bio.

Using kidney cells from new patients at UW and from a commercial vendor, the Texas researchers repeated many of the same experiments and tests previously performed by the UW-Nortis team. As published in Scientific Reports, cells in the Texas A&M study generally behaved similarly to those in the original UW-Nortis experiments, developing into kidney-like structures (in this case, kidney tubules) and performing the same functions as real kidneys.

The scientists also found that the source of kidney cells mattered. There were enough differences in the original study, including in cells’ abilities to metabolize vitamin D and generate ammonia, that the scientists recommended using a commercially available source of cells, including stem cells when possible. Many tissue chip systems already employ induced pluripotent stem cells, which can develop into any type of cell and are a renewable resource.

The researchers also examined several cancer chemotherapy drugs known to be toxic to kidneys, demonstrating the tissue chip model’s usefulness in evaluating drug toxicity.

“The testing centers’ main goal is to bridge the gap between the development of technologies and their actual use in industry to solve real-world problems in drug testing and disease modeling,” said Ivan Rusyn, M.D., Ph.D., Texas A&M toxicologist. “We’re working to provide realistic expectations for using the models.”