Meet Chip: Liver

The liver processes drugs in the body, converting them into their active components. This organ also plays a major role in breaking down substances in the body for energy and for storing energy in the form of starches and fat.

Unfortunately, the liver is particularly vulnerable to damage by toxins (e.g., too much alcohol) and by diseases such as hepatitis. Even properly used drugs can cause the liver to malfunction, either temporarily or permanently. In fact, the liver is the organ most frequently affected by toxic effects of drugs. Current lab-based systems and animal models can be less-than-ideal predictors of liver toxicity in humans.

Testing new drugs in human liver tissue before they are used in people could help predict liver toxicity safely and quickly. Ultimately, the liver chips may accelerate the drug development process and enable the delivery of new and better treatments to patients faster.

Liver on a Chip

Several NIH-supported teams are working on 3-D devices with functional human liver tissue, complete with several types of liver cells. The liver models are designed to mimic the responses of the human liver when used in drug testing.

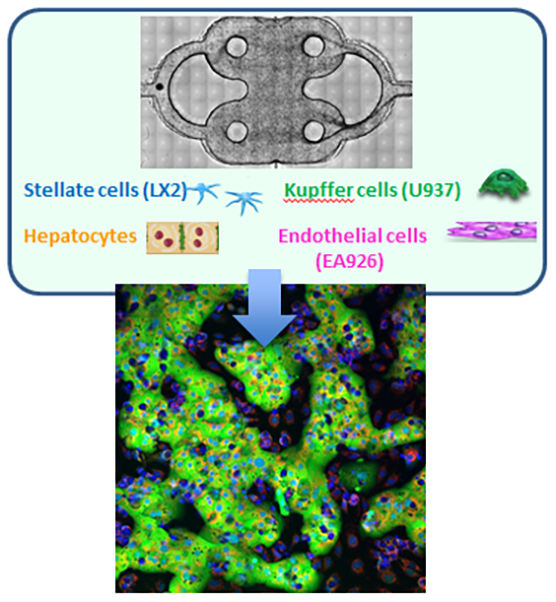

A team at the University of Pittsburgh has created a liver on a chip with four different cell types (i.e., hepatocytes, stellate cells, Kupffer cells and endothelial cells) that self-assemble into plate-like cords, much as they do in the body. The chip generates biochemical and metabolic information and shows stable function. Fluorescent biosensor cells, which can visually indicate changes in cell function, such as cell death or damage from free radicals, are a key feature of the model.

Scientists at Columbia University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are collaborating on the development of a 3-D liver chip. This video shows the liver mix being injected into a channel to form spheroids.

Liver, Heart and Microvessels on a Chip

Another project led by researchers at Columbia University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston University, the Wyss Institute at Harvard University and Yale University involves adding iPSC-derived liver cells to a special biomaterial. This material can provide a 3-D environment to create a liver module that the scientists will integrate with similar modules with cardiac cells or microvasculature. The resulting multi-tissue platform will offer real-time insights into cell and tissue responses for drug screening and predictive modeling of disease.

Looking Ahead

Scientists will likely use the liver on a chip to test experimental drugs. The chip should provide data to accelerate the drug approval process and enable scientists to make new treatments available sooner to patients with liver diseases, including metastasized breast cancer.

Ultimately, scientists aim to link the liver on a chip with other human organ and system models for a variety of studies, including drug and chemical testing. Once the liver on a chip is integrated with chips based on other human organs, scientists will be able to learn more about how the body systems are affected by drugs after being processed by the liver. Researchers also will be able to study liver toxicity resulting from drugs introduced into other organs, such as the gastrointestinal system.