Meet Chip: Lungs

The body’s cells need oxygen to work and grow. They receive this crucial resource through the combined efforts of the lungs and the heart. During a normal day, a healthy person breathes nearly 25,000 times. For the millions of people with lung diseases, however, the simple act of breathing is more difficult. All types combined, lung diseases are the number three killer in the United States.

Many diseases originate in the lungs, but the majority of promising new drugs to treat these conditions fail during testing because they turn out to be toxic. Scientists often must rely on animal studies for early stages of testing, and these models do not always accurately portray how humans will respond later in the testing process. Scientists need better ways to predict how the lungs and the rest of the cardiopulmonary system will respond to potential new drugs.

Lungs on a Chip

Researchers at Harvard University are working to make an innovative model that incorporates lung smooth muscle cells to mimic complex lung conditions in the human body, something that is impossible in animals.

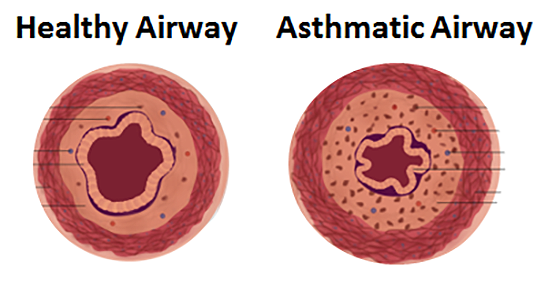

To test this new pulmonary model, the NIH-supported researchers are using chip technology to study asthma. The cells that line the airways are extremely sensitive in people who have asthma. During asthma symptoms, the muscles tighten too much and narrow the airways, making breathing difficult. Using a chip that integrates this muscle tissue, the researchers aim to measure how drugs targeted against one tissue, such as inhaled asthma drugs that target the lungs, affect the other tissues.

Looking Ahead

Using this chip, scientists could screen potential new drugs quickly to test whether they are toxic to the lungs. Data from these tests could help speed the drug approval process and make new treatments available sooner.

The technology also could be part of a bigger, multi-organ system. Scientists could link this chip with other chips — for example, with chips representing the heart and liver — to test how drugs affect multiple organ systems at once.